DCHP-2

Canuck Kanuck, kanaka, kanacka, Cannuck, Canuc  While originating in informal contexts (see DCHP-1, OED-3, s.v. "Canuck", which labels the term "colloq".), only some meanings can be considered informal today. DCHP-2 (December 2016)

While originating in informal contexts (see DCHP-1, OED-3, s.v. "Canuck", which labels the term "colloq".), only some meanings can be considered informal today. DCHP-2 (December 2016)

1a † n. & adj. — Ethnicities, slang, derogatory, historical

a Hawaiian or Polynesian in North America.

While originally deemed of uncertain origin (see DCHP-1, s.v. "Canuck"), work by Mathews (1975) and Adler (1975) offers a transmission scenario that is highly plausible. The term Canuck almost certainly derives from Hawaiian kanaka 'man' (Mathews 1975: 160, Sledd 1978: 176) and was transferred to multiple groups starting around 1800. The first group that the term was applied to were Polynesian sailors, who sailed on North American whaling ships and referred to themselves as kanakas 'men', which the North American sailors used as their name for the Polynesians. The quotations under Kanaka, originally a DCHP-1 entry, predate other meanings of Canuck and support this explanation.

From there, kanak(a) was expanded to other groups, originally triggered by a discriminatory and racist motivation (Adler 1975: 159) (see meanings 1b, 2a, 2b). While the term's history is complex and not yet fully understood, the overall transmission path emerges quite clearly (cf. DCHP-1 Canuck ((n.)) (fistnotes) for previous theories).See also: Kanaka

- Polynesians either settled early in British Columbia and the American Pacific Northwest, or arrived in the East on whaling ships, planting the term in the early 1800s on both sides of the continent with different meanings, i.e. transferring to other foreigners in the East (see meaning 1b), while remaining tied to Polynesians longer in the West.

1b † n. — Ethnicities, historical

a foreigner in North America.

Adler (1975) suggests that perceived darker skin colour was the connection and reason for generalization from meaning 1a to other groups:

"Canuck is given in many standard sources as designating, in Canada, a French-Canadian. Why not a British-Canadian? Could it be (if we assume a connection with kanaka) because skin of the French-Canadian was somewhat darker, more so because of intermarriage with American Indians? Sailors who had been in the Pacific might have applied the term kanaka to darker French-Canadians in Canadian or northwest American or New England ports." (Adler 1975: 159)

The 1835 quotation offers evidence for this argument for New Englanders, who were commonly called by their 19th-century nickname "Johnathan", a point that is made in Mathews (1975: 160). Sledd offers evidence from historical travel reports in which a group of Canadian boatmen was described as "dark as Indians" (1978: 194 fn 11) and of kanakas as "the copper-colored islanders". So it appears that the term was generalized to refer to foreigners more generally, such as the French-Canadian, German and Dutch speakers, who were among the most numerous in 1830s North America. The French (canaque and German languages (der Kanake), have the same meanings, as do other languages, with German acknowledging the South Seas connection with two meanings: "Polynesisan" and as a "coarse term of abuse for foreigners" (ÖWB-42, s.v. "Kanake"). European racism seems to have been the driving force for the dissemination of this meaning, which underwent amelioration in Canada with a dozen years of the 1835 quotation (see meaning 2b).- DARE, s.v. "Canuck", lists the 1835 quotation also as the earliest American attestation and suggests its transition from Hawaiian kanaka into English via "perhaps" Canadian French canaque. The earliest French quotation we were able to find dates from 1866 (Larousse Etymologique 2005, s.v. "canaque"), which is rather late. Our interpretation, see above, would render the transfer from English into Canadian French more likely. Note: The DARE map shows its predominant use in the North-Eastern US, Northern Midwest and Washington State and Oregon.

2a n. — Ethnicities, slang, derogatory, rare

a French Canadian.

Type: 4. Culturally Significant — From meaning 1b, the connection with Francophone Lower Canada was only a question of time: "Since these two groups [Francophones and German speakers] concentrated north of the border the association with Canada came into play as a consequence of the more multilingual nature of early Upper and Lower Canada" (Dollinger 2016a: 17). The meaning "foreigner" is not necessarily a Canadianism, although when it refers to French Canadians alone, it probably is (see below, 2a). Some evidence suggests that this cover-all term for "foreigners" was originally an early American innovation, as the symbolic name "Johnathan" for an American in the 1835 quotation suggests). The association of Canuck with French Canadians is older than its other Canadian meanings (see meanings 2b & 3), dating back to 1746 (see 'Canadian' cross-reference below). In the early 20th century both meanings, 2a and 2b, were common, while today the meaning 2a is comparatively rare (see the 2016 quotation).See also: Canadian ((n.)) peasouper two solitudes

2b n. — Ethnicities

an Anglophone Canadian.

Type: 3. Semantic Change — The 1849 quotation is the earliest unambiguous reference to an Anglophone Canadian. Avis (1983: 5) identifies its setting as New Brunswick and the speaker as English-speaking.- Avis (1983: 5) states that the term Canuck "has been well established in Canada [...] for more than a century. It has no pejorative connotations among Canadians, quite to the contrary. And it is probably used widely among English speakers with reference to all Canadians."

3 n. — Ethnicities, informal

a native or citizen of Canada.

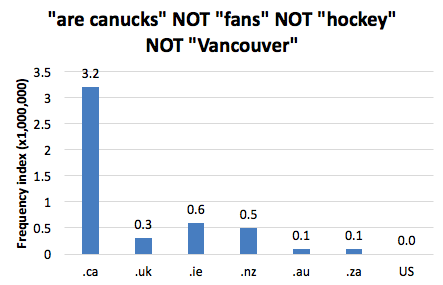

Type: 3. Semantic Change — While the term has undergone semantic amelioration very quickly in Canadian English (see the earliest Canadian quotation from 1849 in meaning 2b), some negative undertones remained in select contexts, e.g. the 1861 or 1931 quotations. These are, however, intermingled early with non-derogatory, though informal uses of the term, e.g. the 1871 quotation. As Chart 1 shows, the term is most frequent in Canada today in non-Sports contexts, which underlines the positive connotations associated with the term in Canada.See also: Jack Canuck Johnny Canuck (def. 1a) true north

- In spite of the definition given in many dictionaries still, the term Canuck as applied by Canadians to themselves is not at all derogatory, quite the contrary. Nor is the term, in modern use, especially associated with French Canadians; again, quite the contrary.

- We have found no evidence that bears out the speculation in the 1963 quotation.

4 adj. — originally informal, now common core

pertaining to Canada.

Type: 3. Semantic Change — In the last third of the 1800s, the term began to be used as an adjective to relate to Canada as a country. Since then the contexts have been expanded to any and all domains.See also: Canadiana (meaning 1) Canuckiana

5 n. & adj. — Hockey

the Vancouver NHL hockey team.

Type: 4. Culturally Significant — In 1945 a Vancouver hockey team by the name of Canucks was formed. It was admitted to the NHL in 1970. This meaning is today the most frequent use of the form.6a n. — rare, historical

Canadian French.

Type: 3. Semantic Change — In connection with meaning 2a, the oldest of the Canadian-specific meanings, the extension from Francophone people to the French language is evident in the 1866 quotation.

See also OED-3, s.v. "Canuck", A.3, for non-Canadian evidence.6b n. — informal, slang

Canadian English.

Type: 3. Semantic Change — In analogy probably to the use of "American" to refer to a language, Canuck has occasionally been used in this specialized sense.See also: Canadian English

7 usually Crazy Canuck — Sports, originally derogatory

a member of the Canadian alpine ski team.

Type: 3. Semantic Change — In the 1970s, Canadian skiers started to take part on the European downhill World Cup circuit. Their improvised material and daring attitude quickly gained them the moniker Crazy Canucks in the foreign press, which was later taken up by the Canadian media (see the 1976 quotation).References:

- Adler (1975)

- Avis (1983)

- DARE

- DCHP-1 s.v. Canuck ((n.)) Accessed 27 Jul. 2016

- Dollinger (2006a) Article Accessed 27 Jul. 2016

- Larousse Etymologique (2005)

- Mathews (1975)

- OED-3

- Sledd (1978)

- ÖWB-42

Images:

Chart 1: Internet Domain Search, 9 Aug. 2016