DCHP-2

sovereignty-association sovereignty association, Sovereignty Association, Sovereignty-Association DCHP-2 (October 2016)

n. — Politics, French relations

a proposal by which Quebec would separate from Canada after negotiating close economic ties, including a shared currency.

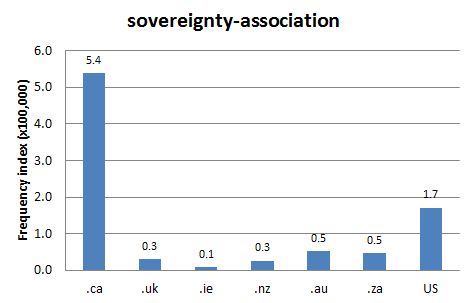

Type: 1. Origin — In 1967, Mouvement Souveraineté-Association (MSA) leader René Lévesque proposed that Quebec become independent while maintaining strong economic ties with Canada (see Canadian Encyclopedia, s.v. "Sovereignty-Association"). The MSA merged with the Rassemblement pour l'indépendance national (RIN) in 1968 to become the Parti Québécois (PQ). The PQ promised a referendum on sovereignty-association as part of their election platform. In 1976, the PQ won the provincial elections under the leadership of Lévesque (see Canadian Encyclopedia, s.v. "Parti Québécois") and held a referendum in 1980, asking voters whether the province should adopt a path toward sovereignty-association. The term is, therefore, of central importance in Canada-Quebec politics. In 1980, 60 percent of voters voted against sovereignty-association and the issue was not pursued further by the PQ until 1995 (see Canadian Encyclopedia, s.v. "Sovereignty-Association", and see the 2008 and 2012 quotations), when a narrow majority of 50.58 percent voted against sovereignty-association. Internet domain searches indicate that the term is most prevalent in Canada (see Chart 1).

See also COD-2, s.v. "sovereignty association", and Gage-5, s.v. "sovereignty association", which are marked "Cdn".See also: separatist ((n.)) Parti Québécois separation sovereignist sovereignty (meaning 1)

References:

- COD-2

- Canadian Encyclopedia "Parti Québécois" Accessed 28 Jul. 2016

- Canadian Encyclopedia "Sovereignty-Association" Accessed 28 Jul. 2016

- Gage-5

Images:

Chart 1: Internet Domain Search, 15 Oct. 2012