DCHP-2

whisky fort DCHP-2 (June 2016)

n. — historical, Western Canada, especially Alberta

an establishment selling or trading whisky illegally to Native hunters; a whisky post.

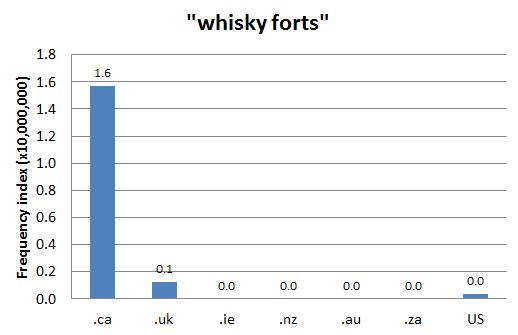

Type: 1. Origin — Whisky forts, primarily located in late 19th-century Alberta, sold whisky and other goods to Aboriginal peoples (see the 1991 quotation). At whisky forts, alcohol was most commonly traded for furs (e.g. buffalo robes) in addition to items such as guns, ammunition and horses (see the 1994 quotation). Trading was done through "a hole a in the wall" (see the 1909 quotation) or "wickets" (see the 1994 quotation), as Aboriginal peoples were not allowed inside the fortified establishments. Whisky forts were established as a result of American expansion, as Aboriginal people, particularly from Montana, were drawn to the "unpoliced southern prairies of western Canada" (see Canadian Encyclopedia). Although there were more than 50 whisky forts operating in Alberta (see the 1991 quotation), the most notorious one was Fort Whoop-up, in Southern Alberta. The earliest attestation of the term describes this establishment (see the 1909 quotation). The end of the whisky fort era is credited to the arrival of the North West Mounted Police (see Mounted Police, Mountie, the 1996 and 2005 quotations, OCCH reference). This term is marked as Canadian origin, appearing in no US or international dictionaries in our set. As seen in Chart 1, the term is most frequently used in Canada.

See also COD-2, s.v. "whisky fort", which is marked "Cdn hist.".See also: Mounted Police Mountie whiskey post

References:

- COD-2

- Canadian Encyclopedia s.v. "Fort Whoop-Up" Accessed 26 May 2016

- OCCH s.v. "Fort Whoop-Up."

Images:

Chart 1: Internet Domain Search, 25 Jul. 2014